SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN: More than 190 nations are hammering out a treaty as industry rushes to cash in

The bluefin tuna is one of the biggest, fastest fishes in the ocean. Its streamlined body can sprint at up to 45 miles per hour in pursuit of its prey. Reaching some 500 pounds, this giant once dominated the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans. But humans have hunted the bluefin for thousands of years. In the last century stocks have been decimated. The Pacific population is now just 2.6 percent of its original size.

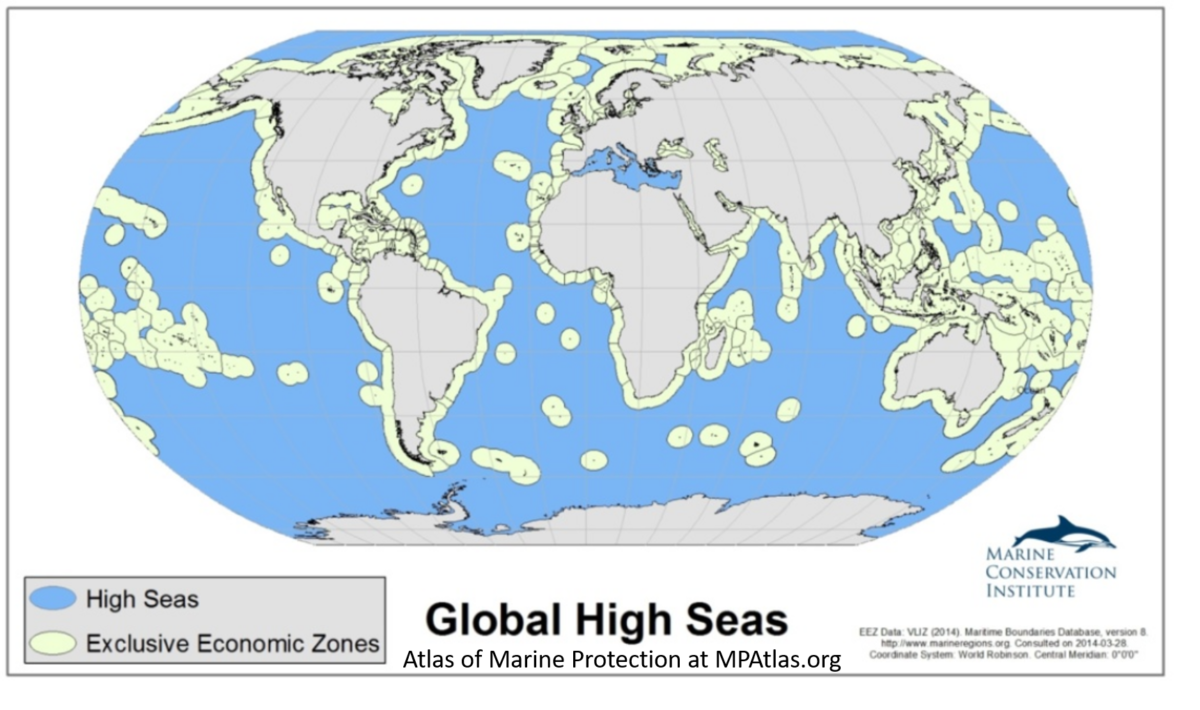

Many other species that live in the high seas—the two thirds of Earth’s oceans that lie beyond national waters—are suffering a similar fate. There is no universal law protecting biodiversity. “This is a massive gap, a literal hole in the middle of the ocean,” says Lance Morgan, president of the Marine Conservation Institute, a U.S. nonprofit focused on ocean protection.

That is about to change. The United Nations is pushing to protect marine life on the high seas with a legally binding treaty by 2020. Delegates from 193 nations are working on it at U.N. headquarters in New York City, through September 17. Yet tension is already in the air. Russia, for example, is vocalizing its opposition to global governance of international waters, a position that could delay or even scuttle the process. And certain nations, from Africa and South America in particular, have made it clear any benefits reaped from international waters should be shared with countries worldwide.